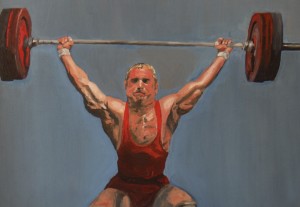

Statistically, more and more people are working out using weights and weight bearing exercise than ever before. Whether it’s to achieve those major biceps for men or to tone and stave off the ravages of osteoporosis for women, fitness with weights is at all an all time high. So, unfortunately, are serious shoulder injuries, most of which occur with upper arm strengthening.

One common problem is an injury to the A-C joint The A-C Joint is the small accessory joint at the top of the shoulder. You can feel it — it is the small bump at the end of your collarbone. A-C stands for Acromio-Clavicular. The acromion is a flat bone at the top end of the shoulder blade. It is nature’s shoulder-pad — a square shaped bone that you can feel at the top of your shoulder. The clavicle is the collarbone. Between the end of the clavicle and the acromion is the A-C joint which plays a major supporting role in the function of the shoulder.”

Both those who work out and their fitness trainers can stress the A-C joint when they do bench-presses and overheads because any exercise that uses a substantial amount weight to move the arm also involves stress to the shoulder. Both of these lifts strengthen the powerful deltoid muscle which lies along the acromion and the clavicle and thus, the stress of heavy lifting can be transmitted to the small A-C joint. People who lift weights for years may injure the A-C joint and develop arthritic degeneration in the area. My patients frequently complain of pain and popping at this joint. I can even hear the pop on examination before x-ray or MRI confirms the injury or arthritic condition.”

The bad news on A-C joint degeneration is that once the damage occurs, it cannot be reversed. There is no cure for arthritis. One solution might be to curtail or give up overhead lifting, but this is usually not an option for dedicated weight lifters. They may abstain from or limit weight lifting, but usually only for short periods of time and rarely long enough to stabilize a serious joint condition. Anti-inflammatory medicines like Aleve, Celebrex and Advil may relieve pain but their effects may only be temporary. A cortisone injection into the A-C joint may also help, albeit temporarily. And neither will relieve the ‘popping’ of the joint. That said, both therapies should be tried prior to surgical intervention.

When A-C joint surgery is indicated, both the pain of the injury and the ‘popping’ sound can be cured with comparatively minor surgery. Quite simply, the end of the collarbone is removed. The painful arthritis and the pressure at the joint are relieved. This often ends both the pain and the popping. The surgery can be done either arthroscopically or through a very small incision at the top of the shoulder. Recuperation is relatively quick – usually two to three weeksto return to normal activity . The good news for the gym set is that there is usually little or no postoperative impairment to the shoulder and patients can happily resume weight lifting and other sports. Some lifters may note slight loss of maximum bench press strength, but this will be offset by relief of painful popping.

Weight lifters can also develop muscular injuries from overuse or overdoing it! One common condition is bicepital tendinitis. “The biceps muscle bends the elbow and it’s long tendon lies in a groove in the front of the shoulder. Tendinitis or inflammation of the tendon can occur with bench presses and ‘dips’. Treatment consists of pain and/or anti-inflammatory medication ; Physical therapy can be useful. Sometimes, a cortisone injection. is necessary.

Older lifters may even rupture the tendon. Sharp pain and a popping sensation may be felt in the front of the shoulder. The pain will eventually subside and usually there will be little or no lasting disability so surgery is rarely necessary.

Another muscle that can tear with excessive stress during bench presses is a tear to the so-called “pecs” – the pectoralis major muscles. A partial tear can be treated with rest and therapy and should heal on it’s own. A complete tear may require surgical repair.

Working out with weights is an important part of many people’s lifestyles. It is, for the most part, an excellent way to help stay fit and an anti-aging boost. That said, it must be approached with care in order for people to gain the maximum benefit from work-outs.” In short, take care of your arms and shoulders and they will help take care of you. If not, your upper body fitness is at serious and potentially permanent risk due to injury.

Please note: these articles are for general information. They are not intended to serve as medical advice or treatment for a specific problem. Diagnosis and treatment of a problem can only be accomplished in person by a qualified physician.